We’ve all read the news by now. Amazon has gone into the library business. And as the Baltimore Sun described it on November 3, this is bad news for libraries.

Amazon’s announcement on November 3 of the Kindle Owner’s Lending Library is a masterpiece of marketing. But the service it offers, at the price point that Amazon is willing to provide it, is a direct shot across the bow of every public library in America.

Any Amazon Prime customer is automatically a subscriber to the new service. There is just one catch. The service only works if you have an actual Kindle! No Kindle app users need apply.

But an Amazon Prime subscription only costs $79 per year, and includes pretty much the same video streaming as Netflix, in addition to 2-day shipping on everything in the Amazon marketplace. For people who do a lot of their shopping through Amazon, this is a great deal. I’m not currently one of those people, but the Netflix to Amazon comparison may make it worthwhile on that cost alone. I can’t say we’re not thinking about it.

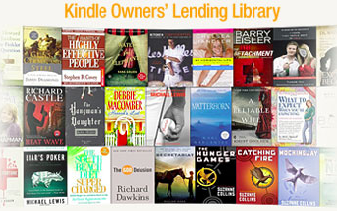

The current cost of the lowest price Kindle is $79. That’s a one time cost. Has anyone noticed that three of the very prominently displayed titles in the Kindle Owner’s Lending Library are The Hunger Games Trilogy? This can’t be a coincidence. The Hunger Games ebooks are not available to libraries through OverDrive. They are available as audio through OverDrive, but not as ebooks. Scholastic does have a deal with Amazon to lend through their lending program, but not through public libraries.

Currently, the “Big Six” publishers do not participate in Amazon’s lending library. That’s Random House, Simon & Schuster, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin and Hachette. But then, two of those six, Macmillan and Simon & Schuster, don’t participate in the library lending space, and HarperCollins’ participation brings up the number 26 and a whole lot of curse words.

But the lending library program is merely another string in Amazon’s bow. Let’s look at what it is again. Any Kindle owner who is already part of Prime Services can borrow one book per month for 30 days, no overdue fees and no hold queues. No muss, no fuss, no additional charges, on a platform they are already familiar with.

What Amazon gets out of this transaction is data, which is also what they get out of allowing Kindle users to borrow OverDrive ebooks from the libraries. They get more data about what people are reading on their Kindles, and they get the opportunity to sell them more Kindle books targeted to them based on that data. Amazon wins big on this.

But I have to contrast the Amazon service with a recent experience at a local library. I decided to finally read the second book in an older mystery series, the Ian Rutledge series by Charles Todd. I listened to Test of Will on a car trip, liked it, and wanted to find Wings of Fire. The library didn’t have it, I don’t want to own it, so I tried interlibrary loan. ILL costs $2. The ebook only costs $7.99. I almost bought it, but I still don’t have a need to own it, and organizing my ebooks is getting to be a chore. I wasn’t worried about how long it would take for the book to arrive, so the month it took to get here was no big deal.

I have three weeks to read it. Not a serious problem for me, I’m used to shorter deadlines, but a nuisance. On the other hand, there’s a 20 cent per day fee if it’s overdue. Since I know the ebook cost $7.99, I’m starting to wonder why I didn’t just buy it, except I’ve already paid $2. And there’s a bookmark in the book to let me know that if I lose or damage the book I’ll automatically be charged $50 until my library settles up with the library that actually owns the book. Since the copy I have is the hardcover, that wouldn’t be $50, but it would be more than $7.99. Obviously, I need to keep the cats away from the book.

I understand about cost recovery. I’ve made all those arguments myself. And multiple times, at that. But I still won’t do another ILL for a book that’s available for under $10 as an ebook. Why? Because the experience is all negative from my perspective. I place the request, and I wait. The book comes in, and I have to figure out when the branch it’s at is open, which is a big issue here. I pay for the ILL, and then I get served with a series of warnings, because the presumption is that I will do something wrong. Those warning labels are attached to the book, just in case I forget them. Then I have to return the book, or I will have to pay again.

The Amazon experience is neutral or positive, and this is true for any ebook purchase from Barnes and Noble and Google and Apple as well. The book is there or it isn’t. Amazon has the special case of the lending library. So someone can borrow it or they can’t. If it’s available for purchase, and I’m willing to pay, I buy it. It automatically downloads to my device, which is already set up from my previous purchases. I’m done. No further charges, no need to go anywhere, no warnings, no fines, no delays. And some potentially helpful suggestions about other books I might like. I’m free to browse further or ignore them and dive into my new book.

Libraries need to be different and good and positive about it. Always. All the time. Whenever we face the public. Are we? If we’re not, Amazon has the potential to do to us what they helped do to Borders.

For those who missed the ALA Virtual Conference, the

For those who missed the ALA Virtual Conference, the