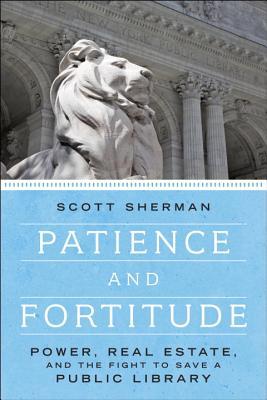

Patience and Fortitude: Power, Real Estate, and the Fight to Save a Public Library by Scott Sherman

Patience and Fortitude: Power, Real Estate, and the Fight to Save a Public Library by Scott Sherman Formats available: hardcover, ebook

Pages: 205

Published by Melville House on June 23rd 2015

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

A riveting investigation of a beloved library caught in the crosshairs of real estate, power, and the people’s interests—by the reporter who broke the story In a series of cover stories for The Nation magazine, journalist Scott Sherman uncovered the ways in which Wall Street logic almost took down one of New York City’s most beloved and iconic institutions: the New York Public Library.

In the years preceding the 2008 financial crisis, the library’s leaders forged an audacious plan to sell off multiple branch libraries, mutilate a historic building, and send millions of books to a storage facility in New Jersey. Scholars, researchers, and readers would be out of luck, but real estate developers and New York’s Mayor Bloomberg would get what they wanted.

But when the story broke, the people fought back, as famous writers, professors, and citizens’ groups came together to defend a national treasure.

Rich with revealing interviews with key figures, Patience and Fortitude is at once a hugely readable history of the library’s secret plans, and a stirring account of a rare triumph against the forces of money and power.

The iconic lions that welcome readers to the entrance of the New York Public Library’s Central Library are named “Patience” and “Fortitude”. This made me wonder about the names of the two equally iconic lions that guard the entrance to the Art Institute of Chicago. Those two don’t have official names, but their unofficial titles are “stands in an attitude of defiance” and “on the prowl”. The difference in names may describe the difference between New York and Chicago, right there.

But the patience and fortitude in this book about the New York Public Library and its most recent step into controversy may be better attributed to those who campaigned against what looks remarkably like a real-estate boondoggle, at least from the outside looking in.

There’s plenty of story here. It begins with the very origins of NYPL, and its rather strange and certainly unique financing. In spite of the name, NYPL was never a public library in the way that most of us think of one. It is not a department of the city of New York, and is not owned or managed by the city. Nor is it an independent taxing district as many libraries are in the Midwest (and probably elsewhere)

Instead, NYPL is a private non-profit entity that owns the buildings of the library, while the city provides funds for personnel and other services – funds which are then administered by the private non-profit. To add to the confusion, the research function of NYPL was never intended to be supported by taxpayer dollars. The intent was for the research library to be supported by donations.

So there are two effectively competing agencies housed uneasily under one administrative roof, while everyone hopes that someone else will pay the bills. A plan which never works, but does provide at least some of the genesis for the mess that NYPL found itself in from 2007 until 2014.

The plan was to sell both the Donnell Library and the Mid-Manhattan Library, and to gut the Central Library’s book stacks, then combine all the services into the single remaining building at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. While the Donnell Library building was sold, the great recession intervened before any more damage could be done.

As the text makes pretty clear, it’s not that there wasn’t a financial crisis that needed to be solved, it’s that in the end, no one except the consultants and their staunchest supporters believed that the solution being proposed would actually solve anything at all. Those in opposition were convinced, and it looks like correctly, that the plan would cause structural damage to the Central Library building, further erode services both to the public and to researchers, and would not actually generate the income necessary to sustain the library. It didn’t help their cause that the claims of damage and rot to the structure of those incredible book stacks seemed overblown, and that no less drastic solutions were even considered.

In the end, it all looked like a grand shell game being played with other people’s money. In this case, NYPL’s money. It also looked increasingly to outsiders that even though no one involved from the library’s side did anything illegal, or made any money under the table, that there was more than a whiff of sweetheart dealing in the way that the properties were going to be, or in the case of the Donnell Library actually were, disposed of.

And no one anywhere should ever believe any consultant on a major building project who claims that there can’t possibly be any cost overruns. There almost inevitably are cost overruns, and the less you expect them, the more ruinous they are.

Reality Rating B+: Before I discuss the gist of this story, I need to insert a caveat or three. I am a librarian, and while I never worked at NYPL, I did work at two of the other city libraries named in the text, Chicago and Seattle. I also served in a middle-management position, not just at CPL and SPL, but also at several middle-sized public libraries, which gave me the opportunity to observe library board meetings on a regular basis, and interact with the boards of trustees at some of those institutions. What I am saying is that I know something about how the sausage is made, and can see similarities to situations I worked in fairly clearly.

So reading this book felt a bit like insider baseball. Some of the people involved were nationally recognized it the profession. And the situations they got themselves into had the ring of familiarity.

The financial situation at NYPL was never very stable. As a librarian, it was considered a great place to have on your resume, but a lousy place to actually work because NYPL did not pay a living wage for the city of New York. Reading the introductory chapters of this book makes it pretty clear why the finances were so precarious.

One of the things that I found amazing was the way that the powers that be at NYPL during this era used their unique situation to suit themselves. They went to the city hat in hand to beg for money for this project, while at the same time frequently ignoring Freedom of Information Act Requests and even demands from the press or the State Legislature for information, and they did it with impunity as a “private non-profit”.

The main part of this saga begins in 2007. This was just before the great recession dropped the bottom out of the real estate market pretty much everywhere. It was also the point where the Google Books project to digitize the collections of great research libraries, including NYPL, was in full swing – and before it ran afoul of the copyright laws in court. Some pundits on the bleeding edge were predicting that libraries would either be all digital or completely obsolete in a relatively short time. Basing the building design on a premise that hadn’t yet been proven looks foolhardy in retrospect. Especially when combined with the notion that “everything will be digitized” when the volume of “everything” that existed prior to the ubiquity of computers is much too high a volume to be digitized within the lifetime of anyone now living.

There has also been a longstanding shift in the library profession to a “give ‘em what they want” mentality. The other side of that coin is when “they” stop wanting something, it’s time to throw it out to make way for something new that “they” will want. This works fairly well in most public libraries, and is an absolute necessity because real estate and shelf space are generally expensive and always finite. But in a research library like the NYPL Central, the intention is to keep a broad and deep collection because we don’t know what some researcher will want 5 or 10 or 50 years from now. But we know that if we don’t preserve it, it won’t exist for that researcher to find.

And then there was the issue at NYPL that the steel book stacks are physically supporting the Rose Reading Room on the top floor. Take out the book stacks and the top floor becomes the bottom floor with a sudden and resounding crash. While there were designs to account for this, none of them seemed as sturdy, robust or even as beautiful and simply functional as the existing stacks.

Part of the plan was that the 3 million volumes housed in those stacks be relocated to off-site storage in New Jersey for better preservation. There was a frequently articulated promise that books would be made available within 24 hours. The problem with this part of the plan was that patrons already had plenty of experience with off-site storage, and 24 hours was known to be a laughable dream. Three or four days was considered an achievable dream, but a week was not unheard of.

As part of this phase of the plan, the powers that be conducted a stealth removal of the books in the stacks, sending them to off-site storage and to private warehouses. The stacks are now echoingly empty, even though the grand plan is dead, and some of the books are completely inaccessible. Others were lost in transition.

There have been any number of libraries and library directors who have found themselves in the midst of hurricanes of controversy over plans to vastly eliminate or move the collections of their libraries. One of the more infamous cases occurred at the San Francisco Public Library in the mid 1990s (see Nicholson Baker’s scathing book, Double Fold, for an example of just how acid the vitriol became). There are more recent stories from the Urbana Free Library in Illinois and the Berkeley Public Library in California. Every librarian knows that massively weeding or otherwise removing the collection is one of the fastest ways to generate negative publicity that libraries can fall into. But the librarians seem to have been left out of the decision-making loop in all of the planning for this great plan.

The NYPL Central Library, with its enduring and patient lions, is a living symbol of the city. It is also a storied place of history, where many scholars and writers did their research and composed some of their greatest work. It’s also a place that, in spite of its often shaky finances, fulfilled every library’s purpose of being the “People’s University” with its doors and its collections open to any researcher or reader who visited its hallowed halls. There were too many people, both famous and forgotten, who loved that building and the purpose it served.

The real estate moguls never had a chance. Just this once, the pen was mightier than the pocketbook. But it was still one hell of a fight.

About Mary Ann RiversMary Ann Rivers was an English and music major and went on to earn her MFA in creative writing, publishing poetry in journals and leading creative-writing workshops for at-risk youth. While training for her day job as a nurse practitioner, she rediscovered romance on the bedside tables of her favorite patients. Now she writes smart and emotional contemporary romance, imagining stories featuring the heroes and heroines just ahead of her in the coffee line. Mary Ann Rivers lives in the Midwest with her handsome professor husband and their imaginative school-aged son.

About Mary Ann RiversMary Ann Rivers was an English and music major and went on to earn her MFA in creative writing, publishing poetry in journals and leading creative-writing workshops for at-risk youth. While training for her day job as a nurse practitioner, she rediscovered romance on the bedside tables of her favorite patients. Now she writes smart and emotional contemporary romance, imagining stories featuring the heroes and heroines just ahead of her in the coffee line. Mary Ann Rivers lives in the Midwest with her handsome professor husband and their imaginative school-aged son.