There are so many things swirling about how libraries purchase ebooks, it’s hard to know where to begin.

The Kansas State Library and OverDrive are butting heads during the renegotiation of the Kansas contract for OverDrive access for public libraries in the state. This is primarily about the platform, or access fee, not about the individual content purchases, which are separate and priced as purchased. But without the platform, no library can access the content.

There are a few issues up front. This particular original contract was negotiated in 2006. The Sony e-reader with e-ink had just been introduced. The Kindle was one year away. Steven Jobs probably hadn’t even dreamed his iPad dream yet. Ebooks for iPhones were still two years away. No one could have predicted the explosion in ebook adoption by the consumer public, let alone by libraries.

There are a few issues up front. This particular original contract was negotiated in 2006. The Sony e-reader with e-ink had just been introduced. The Kindle was one year away. Steven Jobs probably hadn’t even dreamed his iPad dream yet. Ebooks for iPhones were still two years away. No one could have predicted the explosion in ebook adoption by the consumer public, let alone by libraries.

But there is a reason that “may you live in interesting times” is a curse and not a blessing. OverDrive has become the major supplier of ebooks and downloadable audio to public libraries. Unfortunately for OverDrive, it is human nature for people to take shots at whoever is out in front, and in the public library digital market, they are it. To add fuel to the proverbial fire, public libraries are facing the perfect storm of record-breaking usage, heart-rending budget cuts, and an ear-splitting clamor for the digital services that OverDrive represents, with no human, technical or monetary support in sight. For many libraries, ebooks represent another “do more with less” scenario, just with a higher profile.

On top of all of this, platform fees are very strange beasts. When a library subscribes to a database for a year, the database license fee includes both access and content. When the subscription stops, the access stops. It may be expensive, but the concept is relatively simple. In the case of OverDrive, the content is paid for separately from the platform, or access, fee. So what does the platform fee buy?

The platform fee buys access to the content for library patrons, it buys access to the purchasing site so libraries can license additional content, it buys reports so the libraries can figure out what to buy and what not to buy, and it buys customer support for both patrons and libraries,. And that’s where the questions come in. Is the library getting value for money? It’s not about the content. Each ebook and each downloadable audiobook is paid as it is purchased.

At my LPOW, I handled all the digital stuff. All the selection, all the purchasing, all the contracts, all the reports. I’m also a user, but I read way more ebooks on my iPad than I listen to audio on my iPod, mostly because my car is 6 years old but the sound system is too good to rip out and the add-on AUX port just isn’t all that, even though I did add one. Enough said.

For patrons, using the library’s OverDrive site is easier than using NetLibrary–way easier. Not to mention, there’s an app for most devices. But comparative ease of use is a really low bar to get over. And in two years of working with it, I didn’t see much change to the website. There was a tremendous proliferation in the number of compatible devices–but that can easily be said to be a business necessity for OverDrive. If it didn’t natively support the Android and the iPad by this point, how many libraries would have “just said no” in the past 6 months? And how many libraries have had to explain to patrons how to email PDF documents to themeselves to use Bluefire? Also, making changes to the patron interface is very high-touch on the part of OverDrive, and libraries pay for that, whether it is a good thing or a bad thing. On the one hand, the library does not have to do the set up or maintenance, which is good. On the other hand, the library can’t do simple changes for itself, either, like changing the loan period, or creating special topic promotional selections for the holidays, which is not so good, and adds to the cost. On the third hand, (and yes, I know I’ve created a extra-terrestrial here), usage is up, up, up. Usage equals access equals bandwidth. At my LPOW, we had more than tripled bandwidth for all of our internet usage in less than three years, and that cost money. At the same institution, OverDrive is now used twice as much in one month as is was in three whole months when the service first started. The additional bandwidth usage on their end has to get factored in somewhere.

For patrons, using the library’s OverDrive site is easier than using NetLibrary–way easier. Not to mention, there’s an app for most devices. But comparative ease of use is a really low bar to get over. And in two years of working with it, I didn’t see much change to the website. There was a tremendous proliferation in the number of compatible devices–but that can easily be said to be a business necessity for OverDrive. If it didn’t natively support the Android and the iPad by this point, how many libraries would have “just said no” in the past 6 months? And how many libraries have had to explain to patrons how to email PDF documents to themeselves to use Bluefire? Also, making changes to the patron interface is very high-touch on the part of OverDrive, and libraries pay for that, whether it is a good thing or a bad thing. On the one hand, the library does not have to do the set up or maintenance, which is good. On the other hand, the library can’t do simple changes for itself, either, like changing the loan period, or creating special topic promotional selections for the holidays, which is not so good, and adds to the cost. On the third hand, (and yes, I know I’ve created a extra-terrestrial here), usage is up, up, up. Usage equals access equals bandwidth. At my LPOW, we had more than tripled bandwidth for all of our internet usage in less than three years, and that cost money. At the same institution, OverDrive is now used twice as much in one month as is was in three whole months when the service first started. The additional bandwidth usage on their end has to get factored in somewhere.

Another part of what the platform fee pays for is the platform that librarians use to send more money to OverDrive. In other words, libraries pay for the right to spend more money. The best thing that OverDrive could do would be to make it as easy as possible to spend more money. But it isn’t all that easy, especially compared to the tools that we are used to using with print and AV vendors. In fact, the purchasing process has gotten worse in the wake of the Harper Collins mess, because now Harper Collins titles must be searched and purchased separately. But the purchasing side of the equation needs to be updated. There are a lot of simple tools that could help this process, such as standing order plans for ebooks, and standing order plans for the 25 or 50 or 100 most popular authors, pre-publication availability, etc. Or just an automatic plan to get anything that reaches the New York Times Bestseller List. The tools we have available to get stuff available or upcoming on the print side needs to be replicated, because explaining to patrons is painful, as I wrote here not long ago.

Another part of what the platform fee pays for is the platform that librarians use to send more money to OverDrive. In other words, libraries pay for the right to spend more money. The best thing that OverDrive could do would be to make it as easy as possible to spend more money. But it isn’t all that easy, especially compared to the tools that we are used to using with print and AV vendors. In fact, the purchasing process has gotten worse in the wake of the Harper Collins mess, because now Harper Collins titles must be searched and purchased separately. But the purchasing side of the equation needs to be updated. There are a lot of simple tools that could help this process, such as standing order plans for ebooks, and standing order plans for the 25 or 50 or 100 most popular authors, pre-publication availability, etc. Or just an automatic plan to get anything that reaches the New York Times Bestseller List. The tools we have available to get stuff available or upcoming on the print side needs to be replicated, because explaining to patrons is painful, as I wrote here not long ago.

The other piece that libraries get is customer support. Whether customer support is adequate or not is always in the eye of the beholder. Ebook readers and iPads were the gift of this past holiday season. The email I received from a colleague who had given her 95 year old mother a Nook and was requesting the loan period on ebooks be increased to 28 days because her mom couldn’t finish a book in less than that (and 28 days is the standard loan period for a print book at that library) told me that ereaders were in the hands of a population that no one expected. Most libraries have limits to their ability to support the tech behind this revolution. Between all of us at my LPOW, we could figure out a lot of things, but if a patron had a problem downloading to a Palm Treo, we were collectively out of experts, and we called OverDrive. A smaller library would have a smaller pool of in-house users, experts and converts to draw on, but might need just as much customer support, and might have just as many, or more, patrons going directly to OverDrive.

The other piece that libraries get is customer support. Whether customer support is adequate or not is always in the eye of the beholder. Ebook readers and iPads were the gift of this past holiday season. The email I received from a colleague who had given her 95 year old mother a Nook and was requesting the loan period on ebooks be increased to 28 days because her mom couldn’t finish a book in less than that (and 28 days is the standard loan period for a print book at that library) told me that ereaders were in the hands of a population that no one expected. Most libraries have limits to their ability to support the tech behind this revolution. Between all of us at my LPOW, we could figure out a lot of things, but if a patron had a problem downloading to a Palm Treo, we were collectively out of experts, and we called OverDrive. A smaller library would have a smaller pool of in-house users, experts and converts to draw on, but might need just as much customer support, and might have just as many, or more, patrons going directly to OverDrive.

There has to be a better way to make this work. Providing ebooks and other downloadable content is one the fastest growing services that public libraries provide. As the price of ereaders continues to drop, as more and more people use smartphones instead of landlines, reading on a mobile device is going to penetrate even more of every library’s service population. If we don’t get on this bus it will leave us behind.

But it would be better if we drove the bus. Or at least, had a chance at “backseat driving” this bus. For other materials that libraries purchase, we have choices about where to spend our money. There are two major book jobbers, not one. And there are several in the next tier. There are multiple vendors who provide AV material, who also must compete for the library business. Only in the online spaces do we end up in the position where we have to negotiate for the “best one of one”. Even if that “one” were very, very good, competition for our business would make it better for everyone–for the vendor, for the libraries, and for our patrons.

The entire day tomorrow is devoted to adult collection development. There will be talk tables and a keynote speech in the morning. I’m the afternoon speaker. My topic: “The Brave New World of Genre Fiction Selection, the Rap Sheet on the Fiction Vixen, or what the Locus are all these book blogs about?” I’m going to be encouraging collection development librarians to use book blogs as sources for not just reviews, but as trend spotters, to help them find what readers are looking for. I’ve got a whole list of my favorites. I’ve also got a whole lot of slides to show, not just the increasing importance of genre, but what some of those genres are. Steampunk is just so much cooler when you have a picture!

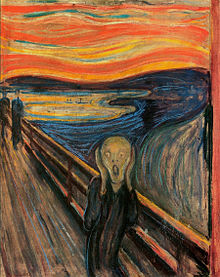

The entire day tomorrow is devoted to adult collection development. There will be talk tables and a keynote speech in the morning. I’m the afternoon speaker. My topic: “The Brave New World of Genre Fiction Selection, the Rap Sheet on the Fiction Vixen, or what the Locus are all these book blogs about?” I’m going to be encouraging collection development librarians to use book blogs as sources for not just reviews, but as trend spotters, to help them find what readers are looking for. I’ve got a whole list of my favorites. I’ve also got a whole lot of slides to show, not just the increasing importance of genre, but what some of those genres are. Steampunk is just so much cooler when you have a picture! On Wednesday I’ll be leading one of the table talks. Wednesday is the children’s and teens CD day. A lot of YA literature these days is genre fiction, particularly of the creepy-crawly variety. And that’s where I come in. I’ll be leading a table talk on the “creature features” of YA fiction, titled “V is for Vampire, W is for Werewolf, Z is for Zombie: the continued trend of the dark, weird and scary in teen literature”. It should be a scream.

On Wednesday I’ll be leading one of the table talks. Wednesday is the children’s and teens CD day. A lot of YA literature these days is genre fiction, particularly of the creepy-crawly variety. And that’s where I come in. I’ll be leading a table talk on the “creature features” of YA fiction, titled “V is for Vampire, W is for Werewolf, Z is for Zombie: the continued trend of the dark, weird and scary in teen literature”. It should be a scream.

For those who missed the ALA Virtual Conference, the

For those who missed the ALA Virtual Conference, the