Format read: ebook provided by the publisher

Format read: ebook provided by the publisherFormats available: hardcover, ebook

Genre: historical fiction, literary fiction

Length: 336 pages

Publisher: Grove Press

Date Released: February 3, 2015

Purchasing Info: Author’s Website, Publisher’s Website, Goodreads, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Book Depository

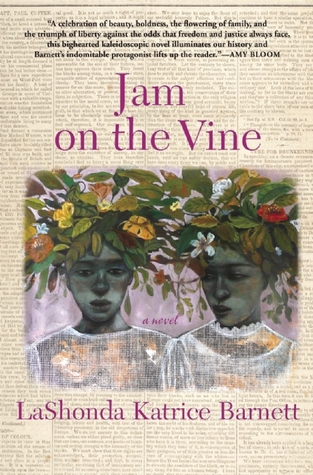

A new American classic: a dynamic tale of triumph against the odds and the compelling story of one woman’s struggle for equality that belongs alongside Jazz by Toni Morrison and The Color Purple by Alice Walker

Ivoe Williams, the precocious daughter of a Muslim cook and a metalsmith from central-east Texas, first ignites her lifelong obsession with journalism when she steals a newspaper from her mother’s white employer. Living in the poor, segregated quarter of Little Tunis, Ivoe immerses herself in printed matter as an escape from her dour surroundings. She earns a scholarship to the prestigious Willetson College in Austin, only to return over-qualified to the menial labor offered by her hometown’s racially-biased employers.

Ivoe eventually flees the Jim Crow South with her family and settles in Kansas City, where she and her former teacher and lover, Ona, found the first female-run African American newspaper, Jam! On the Vine. In the throes of the Red Summer—the 1919 outbreak of lynchings and race riots across the Midwest—Ivoe risks her freedom, and her life, to call attention to the atrocities of segregation in the American prison system.

Skillfully interweaving Ivoe’s story with those of her family members, LaShonda Katrice Barnett’s Jam! On the Vine is both an epic vision of the hardships and injustices that defined an era and a moving and compelling story of a complicated history we only thought we knew.

My Review:

On the one hand, Jam on the Vine is kind of a quiet book. Ivoe Williams reports on the life she sees as much as, or more, than she experiences it herself, especially at the beginning. Until she is faced with a crisis, and then she acts, even when those actions endanger her.

But then again, just living puts Ivoe in danger every single day. She is a black woman in the early twentieth century, a period where Jim Crow held sway in the South, and lynchings were a public spectacle. She could be attacked, raped, imprisoned, beaten, tortured at any time and in any place, while having no recourse to the law on account of her race. Her gender was no protection – it merely provided more ways in which she could be assaulted.

As a story, Jam on the Vine is a number of things, all of them fascinating. It is, first of all, a novel. So when the author says that the story was inspired by the life of pioneering black journalist Ida B. Wells, a look at the historic record shows events that were similar to the protagonist’s life, but not quite the same. Ivoe lives and creates her groundbreaking newspaper just a few years later than her real-life counterpart, in order to pull more dramatic national and international events within its timeframe.

Fiction is great for that.

At the same time, the author uses real newspaper accounts of the time to set the stage, and to emphasize that while Ivoe’s participation in these often horrific events may be fiction, the events themselves unfortunately are not.

But with Ivoe as the center, we are able to view events through eyes that may be very different from our own. She, and the members of her family, personalize history for the reader in the way that a purely factual historical accounting may not.

The story begins with Ivoe as a young girl in central East Texas. Her father is a blacksmith and her mother is the housekeeper for the local white estate owners. Between them, they barely scrape by. Even so, they are slightly better off than their neighbors in the segregated community of Little Tunis, because they own their land.

Ivoe is a dreamer of a child, often lost in her own busy mind. The newspapers that she is allowed to read at the Stark Mansion while her mother is working open her eyes to a world outside her isolated rural town. (White Starkville is certainly better off economically, but still isolated.)

Ivoe dreams big, she dreams of a world outside Little Tunis and Starkville. At the same time, the more she reads, the more she understands that life for her family and friends is more than unfair. The game is rigged and always against them because of their race. The “courtesy” lessons that all the children, but especially the boys, have to have drummed into their heads just for a hope of survival make the reader want to scream. Or cry. (And will remind the reader that things have not changed enough).

They have no rights. Or what few they seem to have they all know can be taken away by the stroke of a white man’s legislative pen, or a lynching.

Ivoe wants to change the world. As she grows up, she finds Little Tunis more and more intellectually stifling, as well as finding herself educated enough to be aware of both the unfairness of it all for her people, and how even fewer options she has as a woman.

Somehow, her parents scrape together enough money to send her to a black women’s college in Austin. For two years, she is able to soar, only to crash to earth upon her return home.

Ivoe is trained to edit, print, publish and totally run a newspaper. But newspapers would rather hire white male high school graduates than her overqualified black, female self. She feels as if her life is closing in. She finally takes one last stab at making her mark by moving to Kansas City, away from Little Tunis. Even though the job she was promised vanishes when her employers learn her race and sex, she perseveres.

She finally commits to the love of her life, and to the work that makes her whole. But by starting a black newspaper in Kansas City, she places herself on the front lines of a battle that is still not won.

Escape Rating A-: Jam on the Vine is a story that will make you think, because the fictionalized events that happen to Ivoe and her family are all real events and real fears that happened in the early 20th century. The road to even as far as we have come is bloody, and we’re not done. The causes that Ivoe (and by extension Ida B. Wells) fought for have not yet been resolved.

Ivoe published reports on the fact that justice in America is not colorblind. While many of us want to believe that is no longer true, a study of the prison population in any state will swiftly prove otherwise.

(Likewise the recent spate of deaths of young black men, often killed by white police officers, shows that we haven’t come as far as we think we have.)

By personalizing the story, the author is able to strike at the heart of both the reader and the still-smoldering issues.

This is also a story about the power of the press to inform and to motivate. Things that we don’t know about don’t move us. They don’t exist for us. In the establishment newspapers of the time, all that the white population read was slanted by the powers that be to continue the status quo that favored them. Black newspapers printed stories that interested their readers, and printed an entirely different view of conditions that the establishment wanted to remain suppressed. (In recent times we have seen the powers that be in Ferguson blame social media for the criticism they received, instead of looking to their own actions.)

One of the characters who moved the plot as deux ex machina seemed underused. (Actually the character is a devil ex machina) Ivoe’s first lover, Berdis, is destructively jealous of Ivoe’s relationship with her journalism teacher, Ona Dunham. While Ivoe and Ona do fall in love after Ivoe leaves school, during their university days Berdis acts like a destructive child and throws away a vital application that Ivoe has asked her to mail with not much reason other than spite. Later in the book, Berdis returns just long enough to set Ivoe and Ona’s house on fire. Literally. Berdis serves as a diabolus ex machina at a couple of critical junctures, but I didn’t get quite enough of her motives.

But I loved this story for the way that it made me think. It made me see the world through Ivoe’s eyes. The best kind of fiction.