Format read: ebook provided by Edelweiss

Format read: ebook provided by EdelweissFormats available: hardcover, ebook, paperback, audiobook

Genre: nonfiction

Length: 432 pages

Publisher: Knopf

Date Released: October 28, 2014

Purchasing Info: Author’s Website, Publisher’s Website, Goodreads, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Book Depository

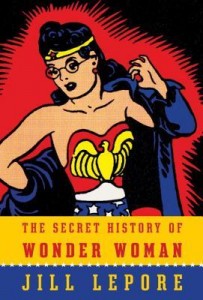

A riveting work of historical detection revealing that the origin of one of the world’s most iconic superheroes hides within it a fascinating family story—and a crucial history of twentieth-century feminism

Wonder Woman, created in 1941, is the most popular female superhero of all time. Aside from Superman and Batman, no superhero has lasted as long or commanded so vast and wildly passionate a following. Like every other superhero, Wonder Woman has a secret identity. Unlike every other superhero, she has also has a secret history.

Harvard historian and New Yorker staff writer Jill Lepore has uncovered an astonishing trove of documents, including the never-before-seen private papers of William Moulton Marston, Wonder Woman’s creator. Beginning in his undergraduate years at Harvard, Marston was influenced by early suffragists and feminists, starting with Emmeline Pankhurst, who was banned from speaking on campus in 1911, when Marston was a freshman. In the 1920s, Marston and his wife, Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, brought into their home Olive Byrne, the niece of Margaret Sanger, one of the most influential feminists of the twentieth century. The Marston family story is a tale of drama, intrigue, and irony. In the 1930s, Marston and Byrne wrote a regular column for Family Circle celebrating conventional family life, even as they themselves pursued lives of extraordinary nonconformity. Marston, internationally known as an expert on truth—he invented the lie detector test—lived a life of secrets, only to spill them on the pages of Wonder Woman.

The Secret History of Wonder Woman is a tour de force of intellectual and cultural history. Wonder Woman, Lepore argues, is the missing link in the history of the struggle for women’s rights—a chain of events that begins with the women’s suffrage campaigns of the early 1900s and ends with the troubled place of feminism a century later.

My Review:

Wonder Woman has often been presented as an icon of feminism. Admittedly, she looks like feminism for the male gaze, with her abbreviated and skin-tight uniform of bustier and increasingly short shorts, but the principles that she espouses, at least when she is being drawn by someone who cares, are generally considered feminist.

If Wonder Woman’s history in the comic books is often convoluted, as DC Comics continually revises, retcons and retools the origin stories for their superheroes, the story of how she was created was possibly even stranger.

There’s also an amount of “small world” feeling that surrounds her creation. She was created by a man who believed that what he was propagating were first-wave feminist values, in spite of the life he lived being something rather different. At the same time, everyone seems to have known everyone. There’s a weird straight line between the creation of Wonder Woman and the invention of the birth control pill. In this history, that line has a couple of kinks in it.

Wonder Woman was created by William Moulton Marston in 1942 during the Golden Age of comic books. Marston’s life was somewhat of a comic book all by itself, but no one seems to have been aware of it at the time, including his children. That’s part of what made this story so fascinating.

In the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, Marston lived at the head of an extremely unconventional household. His wife, Sadie Holloway, embodied the feminist principles that he inserted into Wonder Woman. She was the primary breadwinner, working at the executive level in various industries, including insurance, and was also an editor.

In addition to supporting Marston and their children, Sadie was also supporting the other woman in Marston’s life, Olive Byrne Richard, and the two children Marston had with her. In return for her involvement in this unusual arrangement, Olive Byrne became the caretaker for Holloway’s children with Marston in addition to her own.

Olive Byrne was the niece of Margaret Sanger, the famous (sometimes infamous) birth control advocate, so Marston knew Sanger.

Marston was also the originator of the lie-detector test, even though his design was not the one that went into widespread use.

The story in The Secret History of Wonder Woman is not a publication history of the comic, although there is a bit of that. Instead, it is a biography of the eccentric group of people who made the original Wonder Woman, and a fascinating look at how their unconventional lives and Marston’s unusual psychological theories about love and dominance made their way into the iconic character of Wonder Woman.

Reality Rating B: This is one of those stories that can only be true, because an attempt to fictionalize it would run past anyone’s willing suspension of disbelief.

As narrative, it takes a while to get into, but the journey is definitely worth the ride. At least partially because it’s such a surprise.

Marston certainly believed that the ideas he was promoting in Wonder Woman were aligned with first-wave feminism. After reading this book, I can’t say that I believe it, but I can see that he did. He also had a lot of very strange theories about the power of love and submission both being ultimately stronger than violence and dominance and being what women really needed. Again, not saying I believe it, or that anyone outside his immediate household believed his theories very long, but he did embody those theories in Wonder Woman.

On that other hand, he used both his wife and his mistress as models for different aspects of Wonder Woman’s personality and some of her costume and gadgetry. It also seems like Wonder Woman is the only thing he managed to succeed at, and the rest of the time he was a supposedly enlightened despot overseeing the household that was maintained for his convenience by his two “wives”.

There was a certain amount of bravery on everyone’s part in living a very unconventional life-style, but it seems as if it mostly benefitted him, which doesn’t seem feminist at all. Marston also used the Wonder Woman narrative as a way of poking none too gentle fun at various academics and officials who had derided his theories in the early part of his career.

Whatever he may have voiced regarding the power of women, Marston described all the many and varied ways in which Wonder Woman gets chained and bound, over and over, with a little too much loving detail to sit comfortably with readers who equate Wonder Woman with feminism. It feels like a disconnect between what he said and what he did, and one wonders why no one pointed it out at the time.

All in all, the way that Marston’s real life and theories inserted themselves into Wonder Woman is strangely compelling. The way that first-wave feminism was both promulgated and ultimately rejected by Wonder Woman when it changed hands reflects the change in women’s status after World War II. The backdrop history of the fear of comic books’ influence on children and the rise of censorship is reminiscent of the trials of both television violence and video games that have occurred in more recent times. Some things that have happened before are happening over and over.

This book reads much more like a biography of Marston than a history of Wonder Woman. Still, where those two intersect, and how, is fascinating.

Reviewer’s note: This book is not as long as it initially appears. While reading on my Kindle app, I was 65% completed when the narrative ended and the extensive footnotes began. It’s great to see how well researched the book is, but I thought it had a lot longer to go.