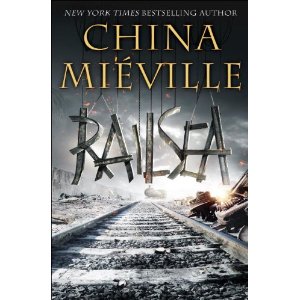

In Railsea by China Miéville, the orphan Sham ap Soorap lives in a tangle, travelling the railsea as doctor’s assistant on the moler Medes. It’s not a job he’s particularly good at, and it doesn’t help he’s not quite sure what he wants to do with himself.

The railsea on which the train Medes travels is a dangerous place — step off the rails, which cover the dry, soft earth-ocean in a Borgesian labyrinth, and you’ll find that the monsters of the deep are rather too close to the surface either for comfort or surviving the next five minutes. However, it has its rewards for those who travel the rails, switching their way from line to line in pursuit of salvage, moldywarpes, or philosophies. You might even find your place in life — or so Sham hopes.

Of course, sometimes you also find something completely unexpected. One day Sham ends up on a crew sent out by the captain to investigate a wrecked train, and comes across some pictures. In short order, Sham finds himself in the middle of a pursuit by pirates, naval trains, and subterrains for what lies behind those pictures — a truth that will change the world.

Escape Rating A: As with the rest of Miéville’s oeuvre, Railsea works on many levels. It’s a rollicking adventure tale worthy of Robert Louis Stevenson, a coming-of-age story, and a treat for those who like wordplay. For example, at one point the Medes finds itself trapped between a siller and the Kribbis Hole (read it aloud to fully appreciate). I’m at best a reluctant user of audiobooks — I tend to listen to them only if I’m faced with a very long drive in areas of the country with spotty NPR coverage — but after reading Railsea, I think I’ll be making an exception and also getting the audiobook.

The book is like the railsea itself, a dense knot of intersecting story lines, changes in points of view, and allusions. The entangling lines of the physical setting matches the complexity of the human setting with its array of diverse island city-states, pirates, salvors, and nomadic Bajjer traveling the lonely sea, to say nothing of the detritus of history and alien influence that litters the world and hints at many untold tales. The book makes it clear that its pages only scratch the surface of a fascinating milieu.

From this knot emerges a meditation on constraint and searching for freedom. The railsea cannot be escaped, seemingly — as I mentioned, stray off the narrow (though not very straight) tracks and you’ll quickly find yourself devoured by the denizens of the soft earth. The high sky is the domain of alien beings too strange and obscure to contemplate. Travel in one direction, and you’ll eventually find the rails looping back on themselves. Pursue your obsession, as Ahab did with Moby-Dick, and you’ll find yourself in the midst of dozens of captains, each with their own “philosophy” that few of them manage to hunt down.

There’s a lot to be said for staying in the thicket — there are lots of interesting things to find there, as any reader of Miéville has come to expect. Once you reach the end, however, you’ll find a rather satisfying breath of fresh air.

![STSmall_thumb[2]_thumb](https://www.readingreality.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/STSmall_thumb2_thumb.png)

Format read: ebook provided by the author

Format read: ebook provided by the author