The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain by Sofia Samatar

The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain by Sofia Samatar Format: eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via Edelweiss, supplied by publisher via NetGalley

Formats available: paperback, ebook

Genres: science fiction, space opera, dark academia

Pages: 128

Published by Tordotcom on April 16, 2024

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org, Better World Books

Goodreads

Celebrated author Sofia Samatar presents a mystical, revolutionary space adventure for the exhausted dreamer in this brilliant science fiction novella tackling the carceral state and violence embedded in the ivory tower while embodying the legacy of Ursula K. Le Guin.

"Can the University be a place of both training and transformation?"

The boy was raised as one of the Chained, condemned to toil in the bowels of a mining ship out amongst the stars.

His whole world changes―literally―when he is yanked "upstairs" to meet the woman he will come to call “professor.” The boy is no longer one of the Chained, she tells him, and he has been gifted an opportunity to be educated at the ship’s university alongside the elite.

The woman has spent her career striving for acceptance and validation from her colleagues in the hopes of reaching a brighter future, only to fall short at every turn.

Together, the boy and the woman will learn from each other to grasp the design of the chains designed to fetter them both, and are the key to breaking free. They will embark on a transformation―and redesign the entire world.

My Review:

This didn’t go any of the places I expected it to go. But the places it went and the themes it explored turned out to be much bigger than I expected – even though they conducted that exploration in the narrowest of spaces.

The space-faring fleet on which both the Hold and the University exist is part of a vast armada of interstellar leeches. This is not a generation ship, although generations of humans have certainly been born and died on its journey.

Instead, this is a human colony designed and engineered to roam the black, much as Quarians were in Mass Effect, but without their tragic, albeit self-inflicted, backstory.

Rather, the human population of this fleet represents humanity in all its dubious glory, greedy and rapacious by design, striving and hopeful in only a part of its execution. The stultifying caste system of Braking Day, Medusa Uploaded and even Battlestar Galactica, as highlighted in the first season episode “Bastille Day” (It took me forever to locate exactly which episode had this plot point but I just couldn’t get the reference out of my head) is on full and disgusting display, particularly in the context of the University.

Not that academia doesn’t do plenty of caste stratification of its very own, and not that it can’t be both blood thirsty and bloody minded – particularly in its small-minded, impractical politics. If an exploration of that appeals and you enjoy SF mysteries, Malka Older’s Mossa and Plieti series, The Mimicking of Known Successes and The Imposition of Unnecessary Obstacles plumbs those depths in all their ugliness while figuring out just whodunnit in a brave new/old world, while Premee Mohamed’s forthcoming We Speak Through the Mountain is a similarly searing indictment of the way that Academe rewrites its own history to obscure its pervasive condescension.

Not that academia doesn’t do plenty of caste stratification of its very own, and not that it can’t be both blood thirsty and bloody minded – particularly in its small-minded, impractical politics. If an exploration of that appeals and you enjoy SF mysteries, Malka Older’s Mossa and Plieti series, The Mimicking of Known Successes and The Imposition of Unnecessary Obstacles plumbs those depths in all their ugliness while figuring out just whodunnit in a brave new/old world, while Premee Mohamed’s forthcoming We Speak Through the Mountain is a similarly searing indictment of the way that Academe rewrites its own history to obscure its pervasive condescension.

Howsomever, as is clear from the above citations, several parts of this story have been done before – and well – if not quite in this combination.

The place I wasn’t expecting it to go was into the metaphysical, quasi-religious depths of Andrew Kelly Stewart’s We Shall Sing a Song into the Deep, which is where The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain gets both its heart and its quite literal depth.

Because the story here, in the end, is both about learning that even people who believe they are free can be conditioned – or fooled – into forgetting that they are just as chained as the obviously and literally named ‘Chained’ people that they are taught to look down upon.

And that it is only by banding together, not through violence but through perception and mindfulness and just plain finding common cause – that they can all be free.

Escape Rating B: This is a story that, at first, seems a bit disjointed. And it does have a sort of metaphysical aspect that seems foreign to its SF story – also at least at first. At the same time, as much as the obvious abuses of the Hold system resemble the contemporary carceral state, the sheer bloody-minded small-minded nastiness of academia sticks in the craw even more harshly – if only because it makes the hypocrisy of the whole, entire system that much more obvious.

This isn’t a comfortable book. It’s beautifully written, compulsively lyrical, and manages to both hit its points over the head with a hammer AND obscure any catharsis in its ending at the same time. I’m not remotely sure how I feel about the whole thing, but I’m sure I’ll be thinking about the spoken and unspoken messages it left implanted in my brain.

Mal Goes to War by

Mal Goes to War by  Because Mal isn’t human at all. He’s a free A.I., or as his people prefer to be called, a Silico-American. He’s merely observing this stupid war from the perspective of an otherwise fairly autonomous but not intelligent drone when he gets the wild and crazy idea to see what it would be like to have a body.

Because Mal isn’t human at all. He’s a free A.I., or as his people prefer to be called, a Silico-American. He’s merely observing this stupid war from the perspective of an otherwise fairly autonomous but not intelligent drone when he gets the wild and crazy idea to see what it would be like to have a body. What hooks the reader, or at least this reader, from the very first page is Mal’s conversation with his two fellow A.I.s, Clippy and !HelpDesk. They’re all snarky to the max, and none of them think much of humanity. To them, we’re entertainment – and we’re bad, boring entertainment at that.

What hooks the reader, or at least this reader, from the very first page is Mal’s conversation with his two fellow A.I.s, Clippy and !HelpDesk. They’re all snarky to the max, and none of them think much of humanity. To them, we’re entertainment – and we’re bad, boring entertainment at that. Court of Wanderers (Silver Under Nightfall, #2) by

Court of Wanderers (Silver Under Nightfall, #2) by  Escape Rating A++: The SQUEE is strong with this review. Let’s get into at least a bit of the why of that fact.

Escape Rating A++: The SQUEE is strong with this review. Let’s get into at least a bit of the why of that fact. A Short Walk Through a Wide World by

A Short Walk Through a Wide World by  Space Holes (First Transmission, #1) by

Space Holes (First Transmission, #1) by  The Emperor and the Endless Palace by

The Emperor and the Endless Palace by  What You Are Looking For Is in the Library by

What You Are Looking For Is in the Library by  As much as I enjoyed the narration, which I very much did, it’s the stories themselves that give the collection its charm, as was true in similar books such as

As much as I enjoyed the narration, which I very much did, it’s the stories themselves that give the collection its charm, as was true in similar books such as  These Fragile Graces, This Fugitive Heart by

These Fragile Graces, This Fugitive Heart by  I also would have loved a bit more about the anarchist and commune movement as it applied to this particular story, because I was basing all of my knowledge and acceptance of the way that part of their world worked on Cadwell Turnbull’s fantastic

I also would have loved a bit more about the anarchist and commune movement as it applied to this particular story, because I was basing all of my knowledge and acceptance of the way that part of their world worked on Cadwell Turnbull’s fantastic  The Fox Wife by

The Fox Wife by  The Butcher of the Forest by

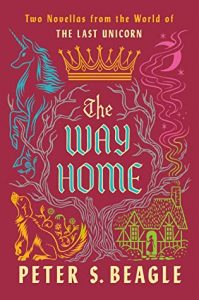

The Butcher of the Forest by  What kept niggling at me through my read of The Butcher of the Forest was that it reminded me, strongly and often, of something else that was not Middle Earth. And that, as it turns out, is the Sooz duology in Peter S. Beagle’s

What kept niggling at me through my read of The Butcher of the Forest was that it reminded me, strongly and often, of something else that was not Middle Earth. And that, as it turns out, is the Sooz duology in Peter S. Beagle’s