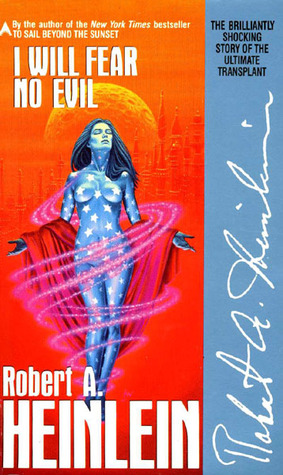

I Will Fear No Evil by Robert A. Heinlein

I Will Fear No Evil by Robert A. Heinlein Formats available: paperback, ebook

Pages: 512

Published by Penguin on April 15th 1987

Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

Johann Sebastian Bach Smith is immensely rich and very old. His mind is still keen, so he has surgeons transplant his brain into a new body the body of his gorgeous, recently deceased secretary, Eunice.

But Eunice hasn't completely vacated her body...

Guest review by Amy:

Robert Heinlein, often dubbed “the Dean of Science Fiction,” is a difficult author to review, in my opinion. My first exposure to Heinlein was To Sail Beyond The Sunset, which I read at a relatively young age. It was his last work, released 1987, and it amazed me in its frank treatment of social, moral, and sexual issues; I’ve often said since that once you’ve read that one, you’re corrupted beyond all redemption, and nothing else Heinlein ever wrote will surprise you. Robert Heinlein’s work–particularly his later work, after the mid-1960s–is nothing if not thought-provoking.

Robert Heinlein, often dubbed “the Dean of Science Fiction,” is a difficult author to review, in my opinion. My first exposure to Heinlein was To Sail Beyond The Sunset, which I read at a relatively young age. It was his last work, released 1987, and it amazed me in its frank treatment of social, moral, and sexual issues; I’ve often said since that once you’ve read that one, you’re corrupted beyond all redemption, and nothing else Heinlein ever wrote will surprise you. Robert Heinlein’s work–particularly his later work, after the mid-1960s–is nothing if not thought-provoking.

For me, at least, I Will Fear No Evil gave me much to think about not only on my first reading years ago, but on my second reading recently. You see, six years ago, I came out as a transsexual, and began the process of transitioning to life full-time as a woman. So this story of a most-unusual sex change has a special sort of resonance with me, and I can read it with a unique set of eyes.

Johann Sebastian Bach Smith is old–in his late nineties, he’s kept going by rather extreme life-support measures, but he can afford it; he’s easily one of the wealthiest people on the planet. He and his attorney come up with a scheme where people with his rare blood type (AB-Negative), will be kept on retainer–if one of them dies of some trauma, he would have his brain surgically moved into the younger body. Before too very long, it happens, and he is stunned to discover that the body is none other than that of his former secretary, a beautiful young woman named Eunice Branca. Shortly, he begins to hear her voice in his head, coaching him on how to be a better woman–but in truth, he doesn’t really need much coaching, it seems.

There’s more to it than that, of course, but I don’t want to spoil the whole thing for you; I’d rather you read it for yourself. There are a few angles I want to talk about, though, for this review.

First, let’s look at the mechanics. When Heinlein had just finished the first draft of this book, he suffered a life-threatening case of peritonitis, which put him on hiatus for two years. It is widely thought that I Will Fear No Evil suffered as a result, through not getting his usual level of attention to detail and polish. I’ve read quite a lot of his work, and I would agree; indeed, the Kindle edition I downloaded contained numerous typos (something that could be an artifact of the digitization process, to be fair), and there were a number of continuity errors that I spotted–in particular, we’re never made entirely certain of Smith’s age. He asserts at several points that he grew up during the Depression of the 1930s, and several times states his age as ninety-five years old, but there are minor discrepancies here and there; none that truly influenced the story, but it was the kind of detail failure that you don’t see often in well-edited works. Overall, our cast is well-developed, interesting, and approachable, and we’re given a sense of time and place that makes clear the state the United States is in–but more on that in a moment. Smith is a lovable, crusty old coot, who’s seen it all and grown cynical, even after his transformation, and I’ve seen this pattern in so many of his later-era male leads that I sometimes wonder if it isn’t the Mary Sue effect–Heinlein casting his male leads as he saw himself. I don’t consider this book Heinlein’s best effort, from this perspective, but it’s still classic Heinlein, in many ways. My one complaint about it is that the main friction point of the story–the “struggle”, if you will–just isn’t much of one. Johann Smith has virtually endless money, so this wild scheme of his actually pans out. Her healing as Joan Eunice is breathtakingly quick–implausibly so–and her transition into life as a woman went remarkably smoothly–wish I had it so easy! With the voice of Eunice helping, and with the assistance of her nurse/maid Winifred, she manages to make the switch very easily; as someone who’s lived through that particular struggle, I’d have liked to have seen more about that process.

What makes Heinlein stories so thought-provoking, for me at least, is the commentary that he blends with his stories. Robert Heinlein had a number of interesting viewpoints on the world around him, and he was not a bit shy about writing them in. Whether it was society, religion, sexuality, space travel, gender roles, or economics, you know he has an opinion, and it shines through in his work. His earlier juvenile works were frequently mellowed somewhat by the audience he was writing for, but even then, he was not above taking a poke at what he saw as a society slowly crumbling around him.

For an example of this, and as a glance at Heinlein’s commentary on society, take a look at Farmer in the Sky, a juvenile work, and contrast it with Friday, a very late work. In both cases–and indeed, in I Will Fear No Evil–we have leads who are seeing society slowly getting more and more intolerable; in Farmer, there is overcrowding and excessive regimented structure, in Friday, it manifested in many small nations, with an overarching corporate shadow-government, while in Evil, we see a world where the government has basically given up; violence and lawlessness are common. Heinlein described himself in his later years as a libertarian, or even a philosophical anarchist; from this story among many others, he makes it clear that the only way to prevent the downfall and collapse of a society is not through top-down government action, but through individuals strong-willed enough to stand against the tide and do something about it. In the present work, we find a nation that has possibly slid past the point of no return. Judge McCampbell, who helps Smith in court with identity hearings that establish that he–no, she–is not, in fact, dead, is a bit of an atavism; he demands that his courtroom be civil at all times, and isn’t afraid to throw everyone out–which triggers a riot, as people have lost the spectacle they came to see. If you read a number of Heinlein’s works, you’ll see his social commentary over and over, and the different paths he places society on to try to stem the tide–few of which actually work.

For an example of this, and as a glance at Heinlein’s commentary on society, take a look at Farmer in the Sky, a juvenile work, and contrast it with Friday, a very late work. In both cases–and indeed, in I Will Fear No Evil–we have leads who are seeing society slowly getting more and more intolerable; in Farmer, there is overcrowding and excessive regimented structure, in Friday, it manifested in many small nations, with an overarching corporate shadow-government, while in Evil, we see a world where the government has basically given up; violence and lawlessness are common. Heinlein described himself in his later years as a libertarian, or even a philosophical anarchist; from this story among many others, he makes it clear that the only way to prevent the downfall and collapse of a society is not through top-down government action, but through individuals strong-willed enough to stand against the tide and do something about it. In the present work, we find a nation that has possibly slid past the point of no return. Judge McCampbell, who helps Smith in court with identity hearings that establish that he–no, she–is not, in fact, dead, is a bit of an atavism; he demands that his courtroom be civil at all times, and isn’t afraid to throw everyone out–which triggers a riot, as people have lost the spectacle they came to see. If you read a number of Heinlein’s works, you’ll see his social commentary over and over, and the different paths he places society on to try to stem the tide–few of which actually work.

The other issue that Heinlein speaks to in this work, understandably, is human sexuality and the role of gender. I’ll say it point blank: by the late 1960s, Robert Heinlein was a dirty old man. By this time in his life, Heinlein was absolutely unafraid to write openly about sexual liberation and freely-practiced sexuality; he was not at all against polyamory, when practiced among consenting people. So much so that I have observed among the “poly” people I know a trend toward modeling their households along a very Heinlein-esque axis. As someone who does not quite grasp jealousy as exhibited in this day and age, I can appreciate his jealousy-free, love-as-you-will approach, and I approve of that aspect of it. Where Heinlein’s notions about sexuality become problematic, for me, is in his too-stereotypical treatment of gender roles; while his female leads are strong and empowered–and most of them, bisexual–they’re almost unilaterally willing to defer to the strong man who is central in their life–or, as in Joan Eunice’s case, at least make it appear so, to him. Heterosexual women in Robert Heinlein’s later works are somewhat uncommon, and it’s taken as a matter of course that any woman who is hetero, or who isn’t an enthusiastic connoisseur of sex, is easily converted. Even the men are not immune to this sort of treatment, but with women, it is just de rigueur. I find this, as well as Heinlein’s total lack of lead characters who are not as sexually active, somewhat frustrating. He paints us an attractive vision of the future where people don’t have to be jealous of their one-and-only, because the notion of one-and-only is accepted as one possibility among many. But if he could have been alive somewhat later, and paired that vision with the enormous breadth of sexuality and gender role experience that the 21st century holds, his vision would have been even more beautiful.

Escape Rating: A-. As I said earlier, this is not Heinlein’s best-crafted work; ask any fan you know, and you’ll probably get several good recommendations for better ones, depending on what you’re looking for. But this one, for me at least, provided plenty of fun story, with interesting people, and the thoughtful and challenging commentary that marks Robert Heinlein as one of the great authors of 20th century science fiction.

Marlene’s Note: A review of one of Heinlein’s works in singularly appropriate for this particular weekend. I will be at the World Science Fiction Convention in Kansas City, and Heinlein’s name will be invoked multiple times in multiple contexts. The context that would be nearest-and-dearest to his heart if he were still among us will be the Heinlein Society Blood Drives, conducted every year at Worldcon in his honor and memory. Some other invocations of his name will be much less charitable, for any possible definition of invocation and/or charitable.

Marlene’s Note: A review of one of Heinlein’s works in singularly appropriate for this particular weekend. I will be at the World Science Fiction Convention in Kansas City, and Heinlein’s name will be invoked multiple times in multiple contexts. The context that would be nearest-and-dearest to his heart if he were still among us will be the Heinlein Society Blood Drives, conducted every year at Worldcon in his honor and memory. Some other invocations of his name will be much less charitable, for any possible definition of invocation and/or charitable.

I read I Will Fear No Evil a long, long time ago. For me, his dirty-old-man-ness overwhelmed the story, which wasn’t nearly as well written as some of his best. I think my first exposure to Heinlein was probably Stranger in a Strange Land, which made interesting reading for a teenager. My favorite work of his is still The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. While some of his attitudes towards women are both on display and slightly obnoxious in Moon, the story as a whole still stands up. And his lesson to Mike on humor, the difference between “funny once” and “funny always” is a distinction I still use whenever applicable.