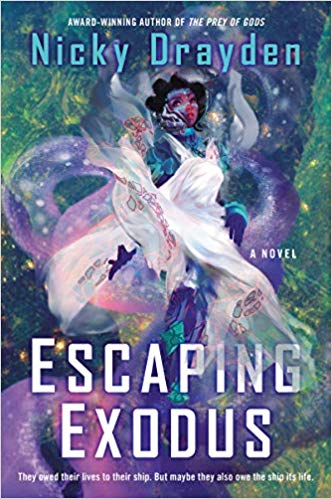

Escaping Exodus by Nicky Drayden

Escaping Exodus by Nicky Drayden Format: eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via Edelweiss

Formats available: paperback, ebook, audiobook

Genres: science fiction

Pages: 336

Published by Harper Voyager on October 15, 2019

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

Escaping Exodus is a story of a young woman named Seske Kaleigh, heir to the command of a biological, city-size starship carved up from the insides of a spacefaring beast. Her clan has just now culled their latest ship and the workers are busy stripping down the bonework for building materials, rerouting the circulatory system for mass transit, and preparing the cavernous creature for the onslaught of the general populous still in stasis. It’s all a part of the cycle her clan had instituted centuries ago—excavate the new beast, expand into its barely-living carcass, extinguish its resources over the course of a decade, then escape in a highly coordinated exodus back into stasis until they cull the next beast from the diminishing herd.

And of course there wouldn’t be much of a story if things didn’t go terribly, terribly wrong.

Escaping Exodus is scheduled to be in readers’ orbit Summer 2019.

My Review:

I don’t know what I was expecting when I picked up Escaping Exodus. Space opera, certainly. And I definitely got that – just not in the usual way.

But this particular space opera has a kind of a biopunk feel, and, speaking of feels, it felt like a story about the differences between parasitism and symbiosis. It also gives a tiny glimpse into all the myriad possibilities of ways that humanity can take a good idea and send it down many, many virtual rabbit holes of disasters and bad decisions. Epically bad decisions.

Oh, and there’s a bit, just a tiny bit, of actually relevant tentacle sex. Now that WAS a surprise.

The story is told from two perspectives that begin close together – diverge widely and wildly – and then come back together at the end. Terribly scarred and terribly scared, but still determined to find their own way forward.

At the beginning, Seske and Adalla are girls on the cusp of womanhood. They have been children, but as the story opens they are forced to take their first steps into adulthood – and away from each other.

Seske is the daughter of the Matris, the leader, ruler and queen of their generation ship. Adalla is the child of one of the worker castes. And there are definitely castes and classes aboard this ship, as well as a permanent underclass and even the equivalent of untouchables. All workers, even the most skilled, are interchangeable and disposable, at least according to the ruling Contour class.

The class system reminds me of the “worms” in Medusa Uploaded. And their treatment does lead to similar results.

Burgeoning adulthood means that Seske has to take her place at her mother’s side, and Adalla must make a place for herself among the workers. They are expected to leave the friendship that has blossomed into love behind and take up their adult responsibilities.

That’s where this story veers into fascinating directions. Because their generation ship isn’t flying through space to a potential “new Earth” even though that WAS the plan when all the ships set out generations ago.

Instead, they have become space parasites, latching their ship onto giant space-faring beasts and cannibalizing all of the beast’s energy, organs and organisms until it is a dry husk, then moving on to the next.

And they’re dying. The beasts are individually dying quickly, but their species is dying out. And they’ll take their human parasites with them.

Unless Seske and Adalla, separately and together, find another way.

Escape Rating B: This is a story that is filled with metaphors for current conditions on Earth and also weaves a fascinating tale of journeys to the stars and all the ways that they can go wrong. Or that humans can do wrong. Or perhaps a bit of both.

At the same time, it feels like this would have been a stronger book if it had had a bit more space in which to develop its world. What we see is amazing and weird and different, but we’re kept at a bit of a remove – at least from the atrocities committed by the privileged classes.

That may be the result of the choice of narrators. Seske, the heir to the “throne” has been an indulged child until the book begins. She’s been protected from all of the terrible secrets and lies, murders and machinations, that her mother has used to maintain her position. That protection gives her a fresh perspective, and allows her to see the rot that supports her mother’s rule.

But she’s been very insulated, and we get a lot more about her rivalry with her sister than we do about how things work, and don’t, and ought to. The way her sister is treated and how that situation came about is brutal and messy and we don’t get nearly enough explanation.

The society is female-dominated, reproduction-restricted, and polygamous. Group marriage is the norm, and families consist of nine adults raising a single child. But I never did quite understand how the relationship between the adults in the group marriage actually worked. Or didn’t.

That the extremely limited resources meant that each marriage could only have one child made sense, but one child per nine adults will result in a diminishing population over time – even without the extremely hazardous conditions that the workers labor under. The female domination of this society is interesting and used to comment on all sorts of things but it’s never explained how they got that way. And we do eventually discover that there are other ships and some are male dominated – and we don’t know how they got that way either. Not that they didn’t make plenty, but different, mistakes along their way.

The history of this diaspora is only hinted at. The hints are fascinating and I wish we learned more.

Adalla’s story feels better developed than Seske’s, because Adalla has the longer and harder journey. It’s through Adalla that we get to see how the workers really live – and die. Adalla herself rises high within the worker castes, and then falls to the lowest of the low.

In the end, both Seske’s exposure of the corruption and Adalla’s rebellion against it lead them to the same place – trying to free themselves and the beasts from an endless cycle of destruction that is killing them all.