A Prayer for the Crown-Shy (Monk & Robot, #2) by Becky Chambers

A Prayer for the Crown-Shy (Monk & Robot, #2) by Becky Chambers Format: eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via NetGalley

Formats available: hardcover, ebook, audiobook

Genres: fantasy, hopepunk, science fiction, solarpunk

Series: Monk & Robot #2

Pages: 160

Published by Tordotcom on July 12, 2022

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org, Better World Books

Goodreads

After touring the rural areas of Panga, Sibling Dex (a Tea Monk of some renown) and Mosscap (a robot sent on a quest to determine what humanity really needs) turn their attention to the villages and cities of the little moon they call home.

They hope to find the answers they seek, while making new friends, learning new concepts, and experiencing the entropic nature of the universe.

Becky Chambers's new series continues to ask: in a world where people have what they want, does having more even matter?

My Review:

This book is the prayer, and we are all, all of us who read this marvelous story, the crown-shy.

Crown shyness is a real-world phenomenon. About trees. Which is totally fitting for this story that features two people – even though one of them doesn’t refer to itself as “people” – who are exploring both friendship and all the myriad wonders of their world together.

Crown shyness is a real-world phenomenon. About trees. Which is totally fitting for this story that features two people – even though one of them doesn’t refer to itself as “people” – who are exploring both friendship and all the myriad wonders of their world together.

Some trees spend their early years growing taller as fast as they can, reaching for the open sky and the sun. Then they start growing outwards, filling in branches and creating their part of the canopy of a forest. You’d think that those leaves and branches up in the canopy would overlap with the trees on all sides, creating a barrier between the sun in the sky and the ground far, far below.

But they don’t. Many species are “crown-shy”, meaning that they somehow know where their limits are and leave just a bit of space, a channel, between where their leaves end and the next tree’s leaves begin. So that the sun does reach the ground to give other denizens of the forest a chance to grow.

The communities in Panga are like that. They grow but so big and no further, so that each village has enough – actually more than enough – to sustain itself and its people. No one needs to want for more.

And that’s what’s at the heart of the Monk & Robot series so far. That question about what do beings want, either as individuals or as a community. What, for that matter, is there to want once society has somehow evolved past our current, endless hunger for more?

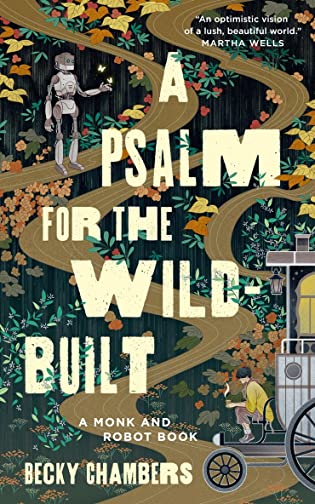

The tea-monk Sibling Dex and the robot Mosscap met in the first book in this terrific series, A Psalm for the Well-Built, because they were both asking variations of that question. Sibling Dex had pulled off the beaten path into the woods because they were in the throes of burnout and were asking themselves if what they were doing was what they wanted to do. If their endless journey was all there was or would be to their life.

While Mosscap was asking itself what had happened to the humans after the robots achieved self-awareness and walked away into the depths of the forest. What did humans need? And more specifically, was there anything that robots could do for them or with them?

The first book followed Dex’ journey deep into the wilderness, into Mosscap’s territory, to a remote location that was once sacred to their god and their service as a tea-monk. This second journey goes the other direction, as Dex and Mosscap head towards the City, home of the University and all its scholars, so that Mosscap can ask its questions of the people in Dex’ world who are supposed to have all the answers.

Only to discover that they’ve both already found their destination. And that what they truly need is each other.

Escape Rating A: If you’re looking for a story that will shed some light into the darkness, just as those crown-shy trees let light through to the forest floor, read A Psalm for the Wild-Built and A Prayer for the Crown-Shy. Because they are the purest of hopepunk, and we all need that right now.

Escape Rating A: If you’re looking for a story that will shed some light into the darkness, just as those crown-shy trees let light through to the forest floor, read A Psalm for the Wild-Built and A Prayer for the Crown-Shy. Because they are the purest of hopepunk, and we all need that right now.

This is a book that asks some pretty big questions, and then lets its two protagonists work out the answers for themselves as they travel through a lovely world that may have solved many of the problems we have today but still doesn’t have all the answers.

As Mosscap discovers, the value is in both asking and being asked the questions. The robot started out with “what do humans need?” The answers that it finds surprise it. In a world where striving for more for more’s own sake seems to have been eliminated, what humans need seems to boil down to one of two things.

Either someone needs help with a very specific concrete issue that either they haven’t gotten around to or for which there isn’t anyone local with the right skills or knowledge. Or, the answer is more existential, where the short version is often something like “purpose” or “fulfillment”. The kinds of things that a person needs to determine for themselves.

As does a robot. Mosscap discovers that it has no answer for itself to its own question. It doesn’t know – at least not yet – what it needs or what its fellow robots need. I sincerely hope that the series will continue, and that we’ll get to follow Mosscap and Dex as they hunt for their own answers.

In the end, this book is an antidote to so much that is happening right now in the world. It’s a walk through light and beautiful places, led by two beings who have learned that friendship is the most important journey of all.

Lost Worlds and Mythological Kingdoms by

Lost Worlds and Mythological Kingdoms by  A Psalm for the Wild-Built (Monk & Robot, #1) by

A Psalm for the Wild-Built (Monk & Robot, #1) by  I was hoping that whatever I got would be as good as

I was hoping that whatever I got would be as good as  To Be Taught, If Fortunate by

To Be Taught, If Fortunate by