‘Poetry’s unnat’ral; no man ever talked poetry ‘cept a beadle on boxin’-day, or Warren’s blackin’, or Rowland’s oil, or some of them low fellows; never you let yourself down to talk poetry, my boy. Begin agin, Sammy.’

On this Boxing Day, I will take the advice of Mr. Weller from the Pickwick Papers and not deliver even a single stave of poetry. Instead, I’ll focus on the natural topic of the day: early warning systems for tsunamis.

The earthquake and tsunami of 2004 in the Indian Ocean took place on December 26th and thus is also known as the “Boxing Day Tsunami”. It killed roughly 230,000 people, making it one of the worst natural disasters of all time.

The epicenter of the earthquake was off the northwestern coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. The resulting tsunami hit coastlines throughout the Indian Ocean, with. Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand suffering the most loss of life.

While it took the tsunami between 15 minutes and several hours to reach various coastlines, unfortunately, most areas had little or no warning that it was coming. A few communities benefited from local knowledge of past tsunamis (or from schoolchildren who happened to remember their geology classes) and evacuated their beaches, but there was no system for detecting tsunamis and broadcasting warnings that covered the Indian Ocean. (And unlike the Pacific Ocean, tsunamis are not particularly common in the Indian Ocean).

Needless to say, after 2004 there were a lot of international efforts to set up a warning system.

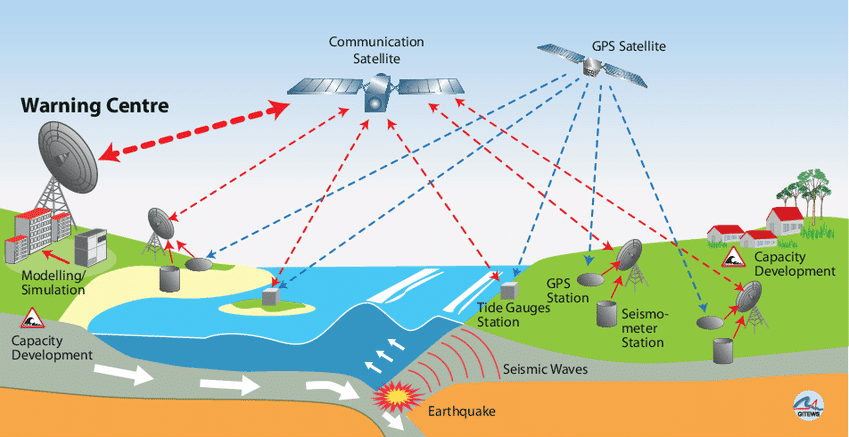

UNESCO’s Indian Ocean Tsunami Information Center‘s website describes the warning infrastructure that has been put in place since 2004. As of today, the three centers of the system (or Tsunami Service Providers (!)) are in Australia, India, and Indonesia. A combination of sensors, 24/7 operations centers, procedures, bureaucracy, and exercises have improved the chances that a tsunami will be detected and warnings relayed in enough time to allow people to flee to higher ground.

And yet: it is a hard problem to not only detect tsunamis but to keep up the effort year after year. The 2018 earthquake and tsunami in Sulawesi, Indonesia killed about 4,400 people. While the the Indonesian meteorological agency (BMKG) did issue warnings, a number of problems led to fewer people actually getting the warning than planned. These problems included:

- The messages were sent by SMS and television broadcast, but tsunami sirens were not activated.

- A network of 22 seafloor sensors and buoys that might have provided an earlier warning had not been functional since 2012 due to lack of maintenance and funding.

- Completion successor to the buoys was stalled due to budget cuts.

- Insufficient data led to the warning getting lifted (arguably) prematurely.

A lot more to do, clearly, and I hope that the people of Indonesia will be better served in the future. However, I want to emphasize that this is a difficult problem: laying all the blame on the BMKG would ignore a lot of structural factors.

Let conclude by circling back to Boxing Day. Traditionally it includes distributing alms to the poor; certainly, when the next tsunami disaster occurs, donating to relief funds would be a good thing to do. However, I can’t say I know where you could effectively donate to improve tsunami warning systems; it may not be the sort of problem that really lends itself to individual charitable giving.