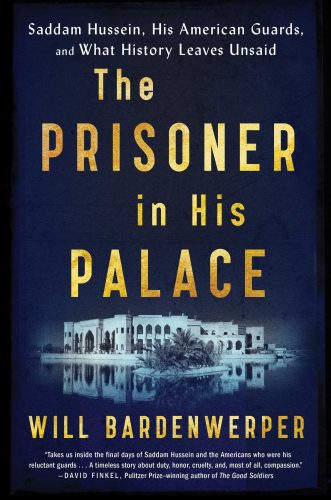

The Prisoner in His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid by Will Bardenwerper

The Prisoner in His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid by Will Bardenwerper Formats available: hardcover, paperback, ebook, audiobook

Pages: 272

Published by Scribner on June 6th 2017

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

In the haunting tradition of In Cold Blood and The Executioner’s Song, this remarkably insightful and surprisingly intimate portrait of Saddam Hussein lifts away the top layer of a dictator’s evil and finds complexity beneath as it invites us to take a journey with twelve young American soldiers in the summer of 2006. Trained to aggressively confront the enemy in combat, the men learn, shortly after being deployed to Iraq, that fate has assigned them a different role. It becomes their job to guard the country’s notorious leader in the months leading to his execution.

Living alongside, and caring for, their “high value detainee” in a former palace dubbed The Rock and regularly transporting him to his raucous trial, many of the men begin questioning some of their most basic assumptions—about the judicial process, Saddam’s character, and the morality of modern war. Although the young soldiers’ increasingly intimate conversations with the once-feared dictator never lead them to doubt his responsibility for unspeakable crimes, the men do discover surprising new layers to his psyche that run counter to the media’s portrayal of him.

Woven from first-hand accounts provided by many of the American guards, government officials, interrogators, scholars, spies, lawyers, family members, and victims, The Prisoner in His Palace shows two Saddams coexisting in one person: the defiant tyrant who uses torture and murder as tools, and a shrewd but contemplative prisoner who exhibits surprising affection, dignity, and courage in the face of looming death.

In this artfully constructed narrative, Saddam, the “man without a conscience,” gets many of those around him to examine theirs. Wonderfully thought-provoking, The Prisoner in His Palace reveals what it is like to discover in one’s ruthless enemy a man, and then deliver him to the gallows.

My Review:

Today is September 11, 2017, the 16th anniversary of the September 11 attacks, otherwise known as 9/11. As though nothing else ever happened, or ever will, that will ring through history the way that September 11, 2001 did. And that’s possibly true. Even the historic hurricane currently sweeping through Florida, while momentous, isn’t quite as earth-shattering. 9/11 was a day where the universe changed, where before and after are sharply and irrevocably separated.

While Saddam Hussein was not one of the architects of the 9/11 attacks, it is certainly possible to trace a direct line from the events of 9/11 to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 that toppled his dictatorship.

This is not a book about the war. Not the U.S. invasion of 2003, nor about the the Gulf War of 1990. Although in some ways it’s about both. A part of me wants to say that the book is about the “banality of evil”, but if there is one thing that Saddam Hussein never was, it is banal.

Instead, this feels like a book about the faces that humans wear, and about one particular human being who wore the face of evil, but only among many, many others. That evil face, the one that the world righteously condemned him for, is not the face that his guards saw. They saw a charismatic and kindly old man. While they were all aware of the evil that he had done, and none ever believed that he was innocent or should be freed, they still guarded someone who was much different. They all went in expecting a monster, only to discover that he was just a man.

The story here is about the twelve young American soldiers, the group that self-deprecatingly named themselves the “Super Twelve”, who had the duty of guarding Saddam Hussein in one of his own palaces during the lengthy course of his trial, right up to his inevitable execution.

The process took well over a year. That’s plenty of time for a group of people to gradually shift from guarded adversaries to respectful acquaintances, if not friends. And that is what happened. Unlike the common perception of “the rich and powerful”, which Saddam certainly was, in his incarceration and forced proximity to these soldiers he acted as a respectful and respected guest, and was treated for the most part accordingly. What small freedoms and little comforts could be provided to the old man, they did. And he appreciated them.

This book is about the relationship that formed among this isolated group. The Super Twelve, the medic who monitored Saddam’s health, the interrogators, and Saddam Hussein. Their camaderie with the prisoner seems odd to the reader, but yet it makes sense. Not only were they all stuck with each other, but they were prohibited from telling anyone what their duty assignment was. The only people they could talk to were each other.

And their prisoner.

Reality Rating A-: This is a hard book to describe, but a surprisingly easy one to get lost in. There are a lot of things packed into this slim volume, and all of them are thought-provoking in one way or another.

It is not really a surprise that the guards became friendly with the prisoner. Or not as the story turned out. If Saddam had been a demanding dictator within the limits of his confinement, the guards would probably have maintained their distance even over the extended time period. But that’s not what happened. Instead, he treated his guards with respect and even affection, and both the respect and affection were returned. They all knew what he’d done, but it didn’t have an effect on his treatment of them or theirs of him.

Instead, many of the guards felt as if this was the first time in Saddam’s life when he was safe. Ironically so, but still, safe. Whether or not he deceived himself about the inevitability of his execution, he was absolutely certain that none of his guards were going to kill him in his sleep – something that had not been true for his entire life. That lack of paranoia led to a lot better rest and attitude – possibly for everyone.

The author does detail enough of Saddam’s atrocities, and there were many, to make the reader certain that the man was the author of countless heinous acts. Even though he may not have seen them as anything more than necessary to cement and maintain his power, there is never any doubt that he was a brutal dictator who used fear and cruelty as potent and effective weapons.

Which does not affect the doubts of any of the soldiers, or of the reader. Not that he deserved death, but, to quote another influential character, “Deserves [death], I daresay he does. Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement. For even the very wise cannot see all ends.”

Even as the trial is being conducted, the sectarian violence in Iraq not only continues, but escalates. Even from the soldiers’ limited perspective, there does not seem to have been a plan for what was to happen after Saddam’s capture. And the manner of his execution only feeds the violence. One of the questions that lingers is whether or not the invasion made anything better. War is easy. Hell, but easy. Regime change, on the other hand, while it is also hell, is damn hard. Especially on the people whose regime is being changed.

What we’re left with is the aftermath, not just for the country of Iraq, but on a personal level for those men who guarded and lived with Saddam Hussein in his final months. Watching a man that they had all developed relationships with go to his death punched an unexpected hole in all their lives. Being forced to stand by while his corpse was desecrated made them all sick and heartsore.

Saddam may have died, but none of them recovered. And their reaction haunts me.