Formats available: hardcover, ebook, audiobook

Formats available: hardcover, ebook, audiobook Pages: 336

on August 11, 2015

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

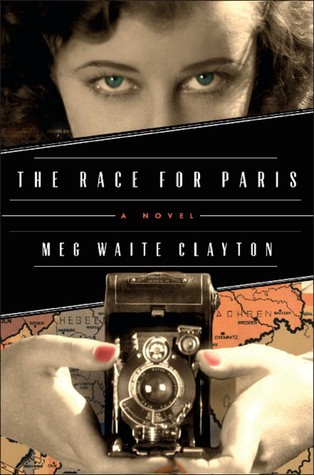

Normandy, 1944. To cover the fighting in France, Jane, a reporter for the Nashville Banner, and Liv, an Associated Press photographer, have already had to endure enormous danger and frustrating obstacles—including strict military regulations limiting what women correspondents can do. Even so, Liv wants more.

Encouraged by her husband, the editor of a New York newspaper, she’s determined to be the first photographer to reach Paris with the Allies, and capture its freedom from the Nazis.

However, her Commanding Officer has other ideas about the role of women in the press corps. To fulfill her ambitions, Liv must go AWOL. She persuades Jane to join her, and the two women find a guardian angel in Fletcher, a British military photographer who reluctantly agrees to escort them. As they race for Paris across the perilous French countryside, Liv, Jane, and Fletcher forge an indelible emotional bond that will transform them and reverberate long after the war is over.

Based on daring, real-life female reporters on the front lines of history like Margaret Bourke-White, Lee Miller, and Martha Gellhorn—and with cameos by other famous faces of the time—The Race for Paris is an absorbing, atmospheric saga full of drama, adventure, and passion. Combining riveting storytelling with expert literary craftsmanship and thorough research, Meg Waite Clayton crafts a compelling, resonant read.

The background of the the story in The Race for Paris is based on the reports of real-life female war correspondents who fought to cover World War II from the front lines, just like their male colleagues. These were women who were told they couldn’t go near the front, because “we don’t have any female latrines and don’t plan to dig any” in spite of the fact that their male counterparts were generally housed in confiscated chateaus with running water and no need for any latrines.

The background of the the story in The Race for Paris is based on the reports of real-life female war correspondents who fought to cover World War II from the front lines, just like their male colleagues. These were women who were told they couldn’t go near the front, because “we don’t have any female latrines and don’t plan to dig any” in spite of the fact that their male counterparts were generally housed in confiscated chateaus with running water and no need for any latrines.

And there were always plenty of available jeeps with drivers to take the guys to the front whenever they asked, but no matter how many spare jeeps were available where the women were segregated, there were never any for them.

While this may sound petty, the facts were that the Army didn’t want women covering the war, and put every roadblock possible in their path. Pioneering reporters and photojournalists like Ruth Cowan, Martha Gellhorn, Dickey Chapelle and Margaret Bourke-White covered it anyway, often going AWOL from their restricted stations in order to cover the war the way it needed to be covered.

The story in The Race for Paris is a kind of amalgamated and fictionalized version of the escapades of those early female war correspondents, as it follows a young newspaper woman, a celebrated photojournalist, and the fully accredited military photographer who provides them with cover and transportation and makes their exploits possible.

This story actually begins in 1994, as journalist Jane Tracy attends a museum exhibit dedicated to her book of the war photography of her friend and companion on that now long ago quest, Liv Hadley. It was Liv’s photographs that told the story, which Jane narrates in her memories as she views the exhibit.

Liv and Jane, at Liv’s insistence, go AWOL from their posting by hitchhiking a lift from a friendly ambulance driver on his way back to the Front to pick up more wounded. He’ll take them out, but once there, the women are on their own.

In the summer of 1944, every reporter in France wants to be the first to reach Paris to cover the liberation of the long suffering City of Light, under Nazi occupation since 1940. The reporter with the first byline from “Free” Paris will make their career. Everyone wants to be first, and the competition is fierce.

At the same time, the camaraderie is abundant. They are all in this together, at least until that last sprint for the finish. Liv and Jane find military photographer Fletcher Roebuck in the same hunt that they are on, but with a difference. Fletcher is photographing German defenses, and is a British officer rather than a civilian correspondent. He can, and does, commandeer transport and supplies. And he is an old friend of both Liv and her husband, newspaper editor Charles Hadley.

Fletcher can’t resist either Liv or her obsession with being the first photojournalist in Paris. At the same time, he can’t bear the thought of Liv and Jane on their own, hopping from company to company in a mad attempt to reach Paris and stay one step ahead of the MPs who are chasing them and return them to the U.S., in handcuffs if necessary.

So Fletcher falls in with the female journalists’ need to cover the war, no matter what the cost is to themselves. And even though they can’t file their stories out of the very real fear that the MPs will track them down by following their transmissions, they still write and photograph the campaign to take Paris from the ground where the soldiers fight, and not from the sanitized and censored press corps camps.

But Paris is not enough.

Escape Rating B: While Jane is telling the story, it is really Liv’s story that she tells. This seems appropriate, because Liv was the photographer, and Jane was the journalist. Liv was the pictures, and it’s an exhibit of her pictures that frames the story, but Jane was always the words.

So Jane finds herself as an observer in the events. She watches as Liv’s candle burns so bright it burns out, and she watches Liv’s feelings about her marriage and fear that while she is in Europe traveling in horrible conditions and sometimes under both enemy and friendly fire, her husband is back in New York with multiple mistresses. And at the same time dealing with his underhanded attempts to get her back home via the MPs, and her own fear that if she isn’t out there taking new pictures and scaling new career heights, she won’t be interesting enough to keep him.

And at the same time, Jane is observing the very mixed-up feelings of their little trio, as Fletcher falls in love with Liv, and Jane falls for Fletcher. The three of them are an emotional train wreck as they trek across Europe with any unit that will have them and not turn them over to the MPs.

Their journey is often harrowing, but frequently lightened by camaraderie with the troops. They write (and film) stories of both hope and brutality, and come away utterly changed. And they live in fear, fear that they will be shot or shelled, and an even greater fear that they will be captured before they finish their self-appointed mission.

Sometimes the story breaks down into a series of incidents, but it feels as if that mirrors both their journey and the feelings of the troops that they covered. The old army motto of “hurry up and wait” is in full force. They hurry to their next destination, and then wait endlessly for something to happen. And everyone was waiting for the liberation of Paris.

At the end, I was left with some mixed feelings. Their journey to cover the war felt very much like the way it must have been. I would have liked more stories about what they covered and how they felt about it. The framing story, while it turns out to have been not just necessary but carried an emotional punch, also led to what felt like a bit too much emphasis on the triangle between Liv, Fletcher and Jane. I wanted more war stories and less romantic emotional angst. There was enough other angst to go around.

But I came away thinking about the conditions under which the female correspondents were forced to work. The men got everything handed to them, and the women were hemmed in and cordoned off and held back at every turn. Then they were arrested when they questioned their treatment. This wasn’t about their safety, they only wanted to work under the same conditions as the male correspondents. If it was safe enough for one civilian, it should have been safe enough for another. Notwithstanding the combat deaths of the 54 war correspondents killed in action in WWII. Only 500 correspondents were accredited, so that’s a pretty big slice of what was supposed to be a non-combatant position.

The way that Liv’s husband treated her rankled. On the one hand, he encouraged her to cover the war. On the other hand, he started rumors and badgered the MPs to restrict her movements and eventually try to arrest her when she broke out. If he had been the one out covering the war instead, while she would have worried just as much, she wouldn’t have encouraged him on one hand and tried to take it all away with the other. Her treatment embodied the whole era – she did every bit as good as job as any of the men, but was constantly told that she wasn’t supposed to be there at all. But they all were, and their contributions kicked open the doors for women war correspondents in (unfortunately) future wars.