Format read: ebook provided by the publisher via NetGalley

Format read: ebook provided by the publisher via NetGalleyFormats available: paperback, ebook, audiobook

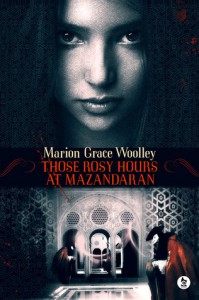

Genre: Gothic horror

Length: 288 pages

Publisher: Ghostwoods Books

Date Released: February 14, 2015

Purchasing Info: Author’s Website, Publisher’s Website, Goodreads, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Book Depository

A young woman confronts her own dark desires, and finds her match in a masked conjurer turned assassin.

Inspired by Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera, Marion Grace Woolley takes us on forbidden adventures through a time that has been written out of history books.

“Those days are buried beneath the mists of time. I was the first, you see. The very first daughter. There would be many like me to come. Svelte little figures, each with saffron skin and wide, dark eyes. Every one possessing a voice like honey, able to twist the santur strings of our father’s heart.”

It begins with a rumour, an exciting whisper. Anything to break the tedium of the harem for the Shah’s eldest daughter. People speak of a man with a face so vile it would make a hangman faint, but a voice as sweet as an angel’s kiss. A master of illusion and stealth. A masked performer, known only as Vachon.

For once, the truth will outshine the tales.

On her birthday the Shah gifts his eldest daughter Afsar a circus. With it comes a man who will change everything.

My Review:

This is a book that teases so many possibilities, but leaves the reader wondering which, if any, might possibly be true. Because it mixes fictional legend with snippets of history, all viewed through the lens of one girl’s brief and bloody life.

And it might be intended as a prequel for The Phantom of the Opera. Or it might all be a dream of history. You’ll still be wondering at the end.

The story is told through the eyes of Afsar, the oldest daughter of Shah Nasser-al-Din of the Persian Empire in the mid-1800’s. Or is she? For that matter, is he? One of the many mysteries is the identity of the Shah and the time period in which this story takes place. Everything is from Afsar’s point of view, what she sees, what she knows. Her perspective is very Persian-centric, court-centric, and child-centric. At the beginning of the story she is ten, and knows little of the outside world.

The way she learns is very skewed, but then, so is Afsar. She is a child of extreme privilege in a poor country, and is both indulged and restricted at the same time.

She eventually learns that little she believed is strictly true. But the truth about herself is equally obscured. While she is not herself a member of her father’s harem, she is also bound by many of its rules on female behavior, as well as rules for the family of the Shah.

When her father brings her a circus for her birthday, she discovers that the world is both wider and stranger than she has ever imagined. She befriends, or perhaps is sought by, the circus’ master juggler, a young Frenchman known only as Vachon. He has become a juggler, among other things, as a way of using his talents rather than being known for his other salient characteristic – Vachon has the damaged face of a human skeleton. He may be Erik, the Phantom of the Paris Opera, as a very young man.

We guess, when the story ends. But we never know.

Vachon teaches Afsar many things, including the art of using a thrown lasso to pluck items out of the air, and how to drop it around the throat of someone she wants to kill. Afsar discovers that she enjoys the sight of blood and the thrill of killing. She has an indulged child’s penchant for killing those who anger her, and those who she deems are too lowly to be missed. She also kills her father’s political and particularly religious enemies.

But her first kill is out of childish jealousy. Vachon has a friend, and Afsar cannot bear it. So she kills his friend and he, in turn, kills hers. The spiral of death that ensues from that one childishly destructive act binds them together for the rest of her life, as they descend into more elaborate death games, and Vachon creates even more bizarre traps and puzzle-boxes in which to carry them out.

Vachon also changes his name to match one of Afsar’s early victims. He becomes Eirik. The leap from Eirik to Erik is meant to be considered, especially after the end of the story.

Afsar’s bloody trail eventually catches up to her. In irony, it happens not because of crimes she actually committed, but out of revenge for one of her earliest victims. And because she has been so self-indulgent as to think that the rules of the court do not apply to her, and that she will not pay if she breaks them.

But then, much of what Afsar believes of herself and the world around her turns out not to quite be true. It may not even be her story. The reader is left wondering. With a slight shudder of horror.

Escape Rating B: This story is very gothically creepy. It is certainly out of the tradition of children who “go bad” and commit horrific acts without thinking of the consequences to themselves because they are too young to realize that they are not above those consequences, or that they cannot get past them.

Afsar believes she is the daughter of the Shah. She isn’t quite old enough, or informed enough, to do the math that would tell her a 22-year-old Shah could not be the father of her ten-year-old self.

Afsar is a mystery to herself and those around her. Keeping herself separate from the other women in the court, thinking herself above them, makes her enemies that eventually bring her down.

Her relationship with Vachon (later Eirik) is part of that separateness. She discovers that she loves to kill. She loves the sight of the blood pooling around her victim. Eirik, equally as lonely as Afsar, shows her both the world outside the palace, and more subtleties in the art of murder.

They come to love each other because they are both equally dark and equally empty. It is both inevitable and ultimately destructive.

The time period in which this story is set is not connected to the wider world within the story itself. Afsar’s frame of reference is completely insular. It is only through comparing events and names to the articles on Persian history in wikipedia that one is able to determine when this story is supposed to take place. I will admit that this drove me a little crazy as I read it, but it does add to the dream-like (or nightmare-like) atmosphere of the story.

Afsar does not see any of her actions as wrong. She knows that she must conceal them, because other people will, but she always feels justified. Or she simply doesn’t care. It adds to the subtle feeling of horror.

The ending, like much of the book, also carries an air of shivering tease. Who was Afsar? Was there an Afsar? How could she be narrating this story? Does Eirik later become the Erik who haunts the Paris Opera? We guess, but we never know.

This story carries an element of seeing something horrible out of the corner of your eye, just like one of Eirik’s puzzle-box palaces. Once begun, I had to see how this one ends, but it definitely creeped me out more than a bit. If that’s your cup of tea, you’ll enjoy the taste of this story. I’ll be over in the corner, shivering.