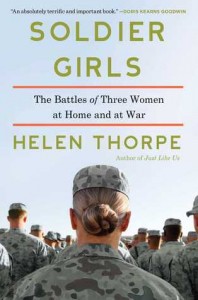

Format read: ebook borrowed from the library

Format read: ebook borrowed from the libraryFormats available: ebook, paperback, hardcover, audiobook

Genre: nonfiction

Length: 417 pages

Publisher: Scribner

Date Released: August 5, 2014

Purchasing Info: Author’s Website, Publisher’s Website, Goodreads, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Book Depository

America has been continuously at war since the fall of 2001. This has been a matter of bitter political debate, of course, but what is uncontestable is that a sizeable percentage of American soldiers sent overseas in this era have been women. The experience in the American military is, it’s safe to say, quite different from that of men. Surrounded and far outnumbered by men, imbedded in a male culture, looked upon as both alien and desirable, women have experiences of special interest.

In Soldier Girls, Helen Thorpe follows the lives of three women over twelve years on their paths to the military, overseas to combat, and back home…and then overseas again for two of them. These women, who are quite different in every way, become friends, and we watch their interaction and also what happens when they are separated. We see their families, their lovers, their spouses, their children. We see them work extremely hard, deal with the attentions of men on base and in war zones, and struggle to stay connected to their families back home. We see some of them drink too much, have illicit affairs, and react to the deaths of fellow soldiers. And we see what happens to one of them when the truck she is driving hits an explosive in the road, blowing it up. She survives, but her life may never be the same again.

My Review:

I picked Soldier Girls as my book to review for Veterans Day because it was incredibly appropriate to the theme of the day. And I heard it was good, which it is. It also surprised me by how much it reminded me of a cross between Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed, and one of Jessica Scott’s military-themed romances that highlight the difficulties of returning home after deployment.

Not that Soldier Girls is either a romance or a book about socio-economic class stratification. But as the story of three women who entered or stayed in the National Guard out of mostly economic or job stratification reasons, and whose service has effects on their civilian relationships, the parallels seem to fit.

The three women in Soldier Girls, Michelle, Desma and Debbie, are all from southern Indiana. They are all part of the same unit, and they all joined before 9/11, which is crucial. Before 9/11, National Guard units did not get deployed into overseas war zones. During the Vietnam Era, the Guard was a lucky and cushy way to sit out the war. None of these women expected to deploy overseas, because that wasn’t the way it worked until the Towers fell. And by then, it was too late for them to get out, even if they wanted to.

Michelle was a college freshman at a tiny branch college campus in a dead-end town. The only jobs available were minimum wage, and it seemed like the only way out was either the military or jail. She already had too many family and friends who had fallen down the slippery slope to drug abuse and alcoholism. Michelle joined the Guard for the college tuition.

Desma was a single-mother who joined on a dare, while drunk. As a single mother in a small town not much better off than Michelle, she stayed for the supplemental income, and the camaraderie.

Debbie was probably the best off economically, but she felt trapped in her pink-collar job as manager of a beauty salon. She wanted to do something with more meaning, and her family had a tradition of military service. So she joined to add purpose to her life. She was the oldest of the group, having joined at age 34, and having served in the Guard for 15 or more years by the time she went to Afghanistan with Michelle and Desma.

From the beginning, their experience of service is different because they are women. Combat positions were not open to women, so there were a limited number of positions available to them. They were also attached and detached to different units, because the specialties they trained in were support positions that were moved around.

Debbie spent a lot of years managing the hot dog wagon at morale events. Desma didn’t receive the proper training that she needed before her second deployment, because the training officer refused to admit she existed or allow any of the men in her unit to even speak with her.

There’s a lot of sexism, and some actual harassment. There is also an extensive use of the buddy system and the whisper network to assist all of them in preventing ever being alone with the worst offenders.

All of them use coping mechanisms for the stress of being deployed that cause major problems when they return home. Michelle and Desma both get into short-term relationships where the other party is married. Debbie copes with lots of booze, but her most emotionally sustaining relationship is with a stray dog. And they all bond with each other and the other women in their unit as a way of sharing this sometimes horrible and yet ultimately life-changing year.

What struck me in their stories was how they each came to the Guard with totally different expectations, and yet only Debbie did it out of love of the military or any actual desire to be a soldier. For all of them, the Guard was a means to an end. But they all found meaning in their friendship, even if (possibly especially if) they didn’t find meaning in the service itself.

Reality Rating A: I was riveted by these stories. The author does a terrific job of showing where each of these women came from, both physically and emotionally, and lets us see why they made the choices they did, and how this one year (or two years for Desma and Debbie) impacts the rest of their lives.

There may also be a lesson in here for recruiters or for whoever is responsible for putting together units for deployment. All the women in this unit created a tight bond that helped sustain them in Afghanistan. They all made it through relatively unscathed. However, breaking the unit up in Iraq had negative consequences both for their preparedness while deployed and for their subsequent re-adjustment back to civilian life.

At the opening, I compared this book to two completely different works, one of fiction and one of non-fiction. Jessica Scott’s series, Coming Home, reflects on the difficulties that soldiers face in returning stateside after deployment in a forward base, the toll that their deployment takes on their families and the good and often bad ways in which they cope. Everything that happens to the women in Soldier Girls was reflected in her fictionalized version. These women experienced so many relationships that foundered or succeeded based on their partners’ ability to deal with what had happened to them. They all make questionable personal choices as they attempt to handle those changes. Debbie’s first grandchild is born, and she can’t be there. Desma, a single-mother, has to deal with making childcare arrangements for her three kids while she is deployed, and then attempting to fix things long distance when her first (and second) attempts fall apart. There are negative consequences of her deployment for all three of her kids that will last throughout their lives, in addition to the disability that Desma brings home from her second deployment.

There is an underlying issue in this book about the nature of the all-volunteer military that is fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, and that’s where the reference to Nickel and Dimed comes in. The military offers financial inducements, like supplementary pay and especially college tuition, that are designed to appeal to people, both men and women, in Michelle’s and Desma’s situations; those who want to get out of a dead-end or need a financial boost to make ends wave at each other. This dovetails with Barbara Ehrenreich’s discovery (whatever you think of the way she did it) that it isn’t possible to live on a minimum wage job and still cover your rent, utilities, food and expenses. If she had performed her experiment in southern Indiana instead of Minneapolis, she could have heard Michelle or Desma discussing their reasons for joining the Guard, especially the financial incentives. It’s a sobering thought.

Thank you for posting this review today. (Surprised how many of my usual read-while-I-have-coffee sites are business as usual.).

The Nickel-and-dimed aspect of why people join is a huge deal – especially, frankly, as the soldiers themselves are nickel and dimed. I joined the military for college tuition, but I did it via the ROTC program and came out an officer, which made a huge difference in pay and civilian opportunities. It was also the 90s, way before the repeating deployment cycles of the past decade, so I was largely able to structure a civilian life around a continuing Army Reserve commitment, but that too has changed.

There are so many important conversations about these issues that the politicians, policy makers, and even the highest ranks of the military aren’t having – I don’t see the pace of deployment as a political issue, but as basically an HR issue that the top of the military won’t step up and address. Sometimes I think that as long as there are enough financially struggling people in the US to fill the military’s ranks, then the top doesn’t care about improving anything, because there will always be someone who needs a second job and college tuition.

It’s disheartening. But thank you for reading and reviewing this.